An Academic Question by Barbara Pym

4/5

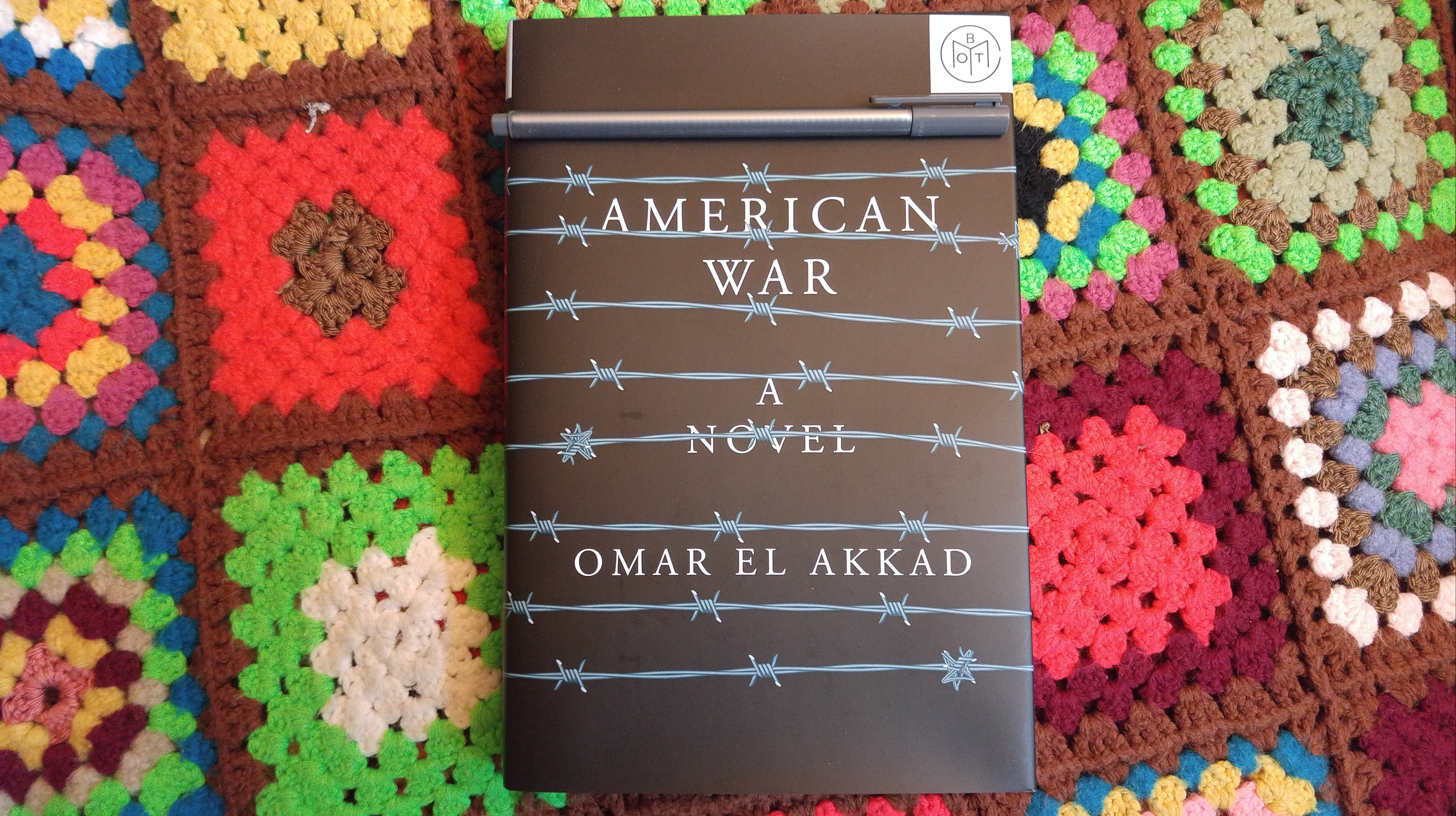

After finishing American War (which I wrote about here), I felt strongly in need of something cozy and charming to ease me back into reading about non-apocalyptic settings and themes; Pym’s An Academic Question was just the ticket. This is my second novel by Pym, and while I didn’t love it quite as much as her much more famous Excellent Women (which I adored), I did enjoy it. An Academic Question wasn’t published during Pym’s lifetime, I believe, but was, rather, cobbled together from two drafts (one that took a more fashionable wry and witty tone and one which was written more earnestly) and put out posthumously by a friend and biographer of Pym’s, Hazel Holt. I knew this little history before I began my reading, so I was a tad distracted looking for evidence of this origin story in the finished manuscript, but if there were awkward jolts between styles, they were few and far between. What I remember of Excellent Women is that it is this mixture of sardonic earnestness which rather marks Pym and drew me to her, and while that same blend doesn’t come off quite as well in this novel, it still achieves an amusing and sympathetic effect.

An Academic Question is about a young woman, Caro, who is married to Alan, a junior professor at “a provincial college” who is rather desperately casting about for his big break in the field of Anthropology. Caro, with the help of their au pair, Inge, cares for their daughter Kate, and is friend to a number of their small town’s more endearingly eccentric characters (my favorite is Dolly, a secondhand bookshop owner who obsesses over hedgehogs and uses her pensioner’s money to buy scandalously expensive brandy); otherwise, though, Caro is rather unfulfilled. She can’t decide on a life’s work, Alan seems to be either having or planning to have an affair, and the university events she’s expected to attend are becoming increasingly difficult for her. Her chief problem in the novel, though, unfolds when Alan makes her an accomplice to the theft of a dying missionary’s private manuscript which Alan uses to advance his own career and then foists off on Caro.

There are many academic questions explored within the novel: What are the moral limits when it comes to expanding the world’s store of scholarly knowledge? What about just when it comes to expanding one’s own career prospects? What are the duties of the spouse to the academic, and what are the duties of the academic to the nonacademic? Is a life devoted entirely to scholarship necessarily the best life? Like all good novels, An Academic Question does not answer such questions, or even directly pose them, but merely highlights them within a context for the reader’s inspiration.

That face! I think she’s starting to develop a slight resemblance to Salvador Dali.

Since I finished grad school a few years ago, novels with academic settings or academes as main characters have been a bit taboo on my reading list. I tend not to find them charming or witty or fulfilling the suggested requirements of any positive adjectives really. There are a few exceptions (I read Moo by Jane Smiley while still in grad school and I loved it; more recently I added A.S. Byatt’s Possessions to my list of favorite books ever), but for the most part I have no stomach or sympathy to spare for such novels because they remind me of what a miserable time I had in grad school. Perhaps with my enjoyment of An Academic Question I’m getting beyond all of that, or perhaps the appeal of this book lies in the fact that it’s written from the perspective of a person who is a bit of an outsider to academia despite being thrust into its world on a daily basis. This is a position I often feel myself to be in, because while I happily and totally left that world behind me, I’m still the daughter of academics and many of my friends remain linked with academia in some fashion. So, I found Caro to be very relatable on this level, and I sympathized a lot with her anxieties about meeting the expectations of her husband and his peers regarding the living of a fulfilling life and the issue of who gets to decide what that means.

Anyway, I enjoyed this book and I’m looking forward to reading more Pym! I’ve already got a few more of her books on my shelf just waiting to be devoured, but I’m open to suggestions! Any particularly good Pym novels I should be seeking out? What about any other novels that might help re-open me up to academia as subject matter?